The #LoveLittleRock banner was flying high over Seattle, and Millie Ward was smiling in her advertising office in Little Rock, floating on Cloud 9.

Ward was “overjoyed” with the response Stone Ward’s “Hey Amazon” letter stirred, creating a media sensation out of Little Rock’s decision not to plead for the online retailer’s second North American headquarters.

“It’s been an amazing, unbelievable response,” Ward said, smiling again.

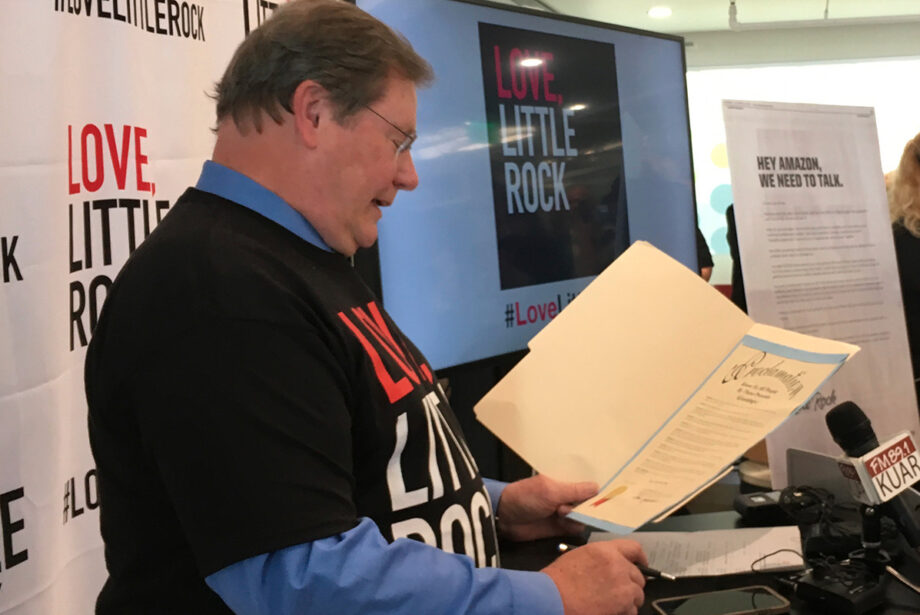

Odds are you heard about how Little Rock “broke up” with Amazon with a full-page ad in the Washington Post (the usual cost is $80,000, but the Little Rock Regional Chamber said it got a deal). The ad was a love letter, Ward said, but it was actually a rejection note: Amazon and Little Rock may not be suited for each other, it said, but they have a lot going for them, and here are some of Little Rock’s strengths for business. The ad was accompanied by a video, a website and a social media push, even a plane flying a “Hey Amazon” banner over Seattle.

Other cities, including San Antonio, also said they weren’t right for the $5 billion, 50,000-worker Amazon project and all of its infrastructure demands. But no city said no thanks with the panache of Ward’s campaign, “Love, Little Rock.”

Working free of charge for the Little Rock Regional Chamber, Stone Ward cagily chose the Post for its ad because the paper is owned by Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos.

“It’s not you, it’s us,” the tongue-in-cheek message began, going on to acknowledge some of the city’s shortcomings in Amazon’s eyes, like the lack of an international airport. But the letter also laid out central Arkansas’ lures for other companies, including natural beauty, a business-friendly vibe, a tech-savvy workforce and a creative culture.

“Jay Chesshir saw this as an opportunity to get positive play for the city among economic development influencers,” Ward said, referring to the chamber president and CEO. “His goal was to get people outside the city — businesspeople, consultants and influencers — to notice Little Rock, to think positive things about us, to like us.” She said it was Chesshir’s idea to make news by not going after Amazon. But she had no idea what a splash she’d make.

By 2:30 p.m. on Oct. 23, four days after the campaign began, it had generated news and digital impressions worth $1.7 million in advertising, according to Cision, a tool agencies use to measure the value of free publicity now often called “earned media.” “We had more than a billion impressions, and we were in the top 10 stories on the ABC news website.”

Little Rock drew news coverage by NPR, which interviewed Mayor Mark Stodola, as well as The New York Times, Fox Business and The Boston Globe. Andrew DeMillo’s report went out on the Associated Press wire, and Fortune magazine shouted, “Hear that, other companies? Little Rock is available.”

The whirlwind week started when Ward got a call from Chesshir, who thought that while 238 cities were pitching to land Amazon, Little Rock could make some noise by saying no. Chesshir said he got the idea from Jonathan Semans of CDI Contractors. Ward promptly called Del Boyette of Boyette Strategic Advisors, who gave a thumbs up. Ward, Boyette and Chris Marsh brainstormed over lunch at Canvas, the restaurant at the Arkansas Arts Center, before Ward convened a 20-member team on a Sunday, on their own time, to put 200 ideas on the board. “One of them was a Washington Post ad,” Ward said. “Another was a plane flying a banner over Seattle, but we had enough ideas to do one a day for nearly a year.”

Ward turned to her partner and husband, Larry Stone, and several writers to refine the breakup letter idea. “It was a magical once-in-a-career kind of thing,” she said. She and Stone quickly decided to work pro bono, but they hope to lead a paid campaign for the chamber later.

Some detractors at home pointed out that Little Rock and Amazon weren’t actually in a relationship, and others saw a “corny” publicity stunt. The Arkansas Times even wrote its own “Dear Little Rock” letter, urging the city to work on its serious problems, including crime and a segregated school system.

“I think it’s sad,” Ward said. “I know there are people over at the chamber working every day on the city’s problems. No city is perfect, but when you’re selling economic development opportunities, you focus on the positive. And all of the out-of-market coverage we’ve seen has been positive.”

Chesshir dropped by Stone Ward toward the end of the interview, and offered his bottom line. “Hundreds of cities were involved in this process, and in the end, only two will be remembered,” he said, “the winning city, and Little Rock.”