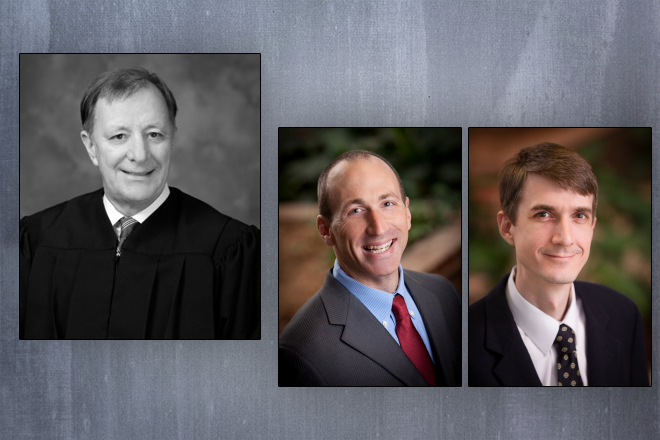

Judge P.K. Holmes III said in a recent order that he has "a strong impression" that attorneys Josh Sanford and Steve Rauls, shown in order on right, have directed most of their efforts "toward obtaining a settlement for Plaintiffs that includes a large fee award for attorneys appearing from the Sanford Law Firm."

Two Little Rock lawyers have asked the chief federal judge for the Western District of Arkansas to reconsider sanctions he imposed on them after a string of cases in which he was critical of their law firm’s work.

In June, Judge P.K. Holmes III sanctioned lawyers Josh Sanford and Steve Rauls of the Sanford Law Firm because two of their clients failed to show up for depositions, ordering them to pay related expenses. They are representing plaintiffs in a 2016 lawsuit alleging that the Gregory Kistler Treatment Center Inc. of Fort Smith failed to pay overtime.

Holmes said in a three-page opinion and order that he was familiar with the lawyers because they appeared before him in several cases related to the Fair Labor Standards Act. In many of those cases, Holmes reviewed settlement agreements and approved or denied attorneys’ fees and costs.

“This experience has left the Court with a strong impression that Sanford and Rauls have very little interest in engaging in or responding to discovery, and that most of their FLSA litigation efforts are instead directed toward obtaining a settlement for Plaintiffs that includes a large fee award for attorneys appearing from the Sanford Law Firm,” Holmes wrote.

In some of the cases before Holmes, he slashed the request for attorneys’ fees or rejected their settlement agreements.

Sanford and Rauls asked Holmes in a July 13 filing to reconsider his sanctions. “The award of sanctions is based on a misunderstanding about disclosure of client communication, and Plaintiff’s counsel apologizes for the misunderstanding,” Rauls and Sanford wrote.

They also said there’s no evidence they did anything wrong in the Gregory Kistler Center case or in any other cases.

The attorneys said they do participate in discovery and have participated in more than 20 depositions this year alone. In addition, they said, they represent low-wage workers in FLSA cases and “frequently take discounts on their fees.”

Holmes, they said, had approved their proposed settlements in other FLSA cases and praised their work. Holmes found ‘“the parties have engaged in extensive document and deposition discovery’ — a finding completely inconsistent with the Court’s Opinion and Order suggesting that counsel for Plaintiffs have failed to engage in or respond to discovery,” the attorneys said.

In an email to Arkansas Business, Sanford said it was common for Holmes to scrutinize agreements, and he welcomes it. “That is a laudable part of the Court system,” he wrote. “We are sure Judge Holmes welcomes the scrutiny that comes from an appellate review just the same, as that is part of the system, too.”

As of early Thursday afternoon, Holmes hadn’t ruled on the motion for reconsideration. An attorney for Gregory Kistler, S. Brent Wakefield of the Barber Law Firm in Little Rock, has asked for $5,336 in attorney’s fees and costs of $750 in connection with the missed depositions. Holmes also hasn’t ruled on Wakefield’s request, and Wakefield declined to comment.

Sanctions by federal judges are relatively rare; they follow lawyers into other jurisdictions and must be reported to their liability insurers. Holmes has been willing to sanction before. Two years ago he reprimanded attorney John Goodson of Texarkana and other lawyers for engaging in “forum shopping” in a class-action case. Goodson and others appealed the order to the 8th U.S. Court of Appeals, which overturned Holmes’ ruling.

Other Concerns

Holmes has had other concerns with other cases handled by Sanford and Rauls.

With Fair Labor Standards Act cases, unlike most civil lawsuits, settlements must be approved by a judge because the class members are then bound by the terms of the settlement, said Ruben Garcia, a professor of law at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and co-director of the UNLV Workplace Law Program.

“It prevents people from coming later and saying that they didn’t have good representation, or they didn’t get notice of the case,” he said. “So it’s a way of preserving the finality for the players and for the employees.”

Garcia said that “it seems rare that a judge doesn’t approve” an FLSA settlement. But even if both sides agree, he said, a judge might reject a settlement that’s not in the best interest of the plaintiffs. “The judge sometimes has the interest of the plaintiffs in mind,” Garcia said.

Holmes recently rejected settlement agreements Sanford and Rauls reached in a 2017 case against Baldor Electric Co. of Fort Smith (now ABB) over allegations that it didn’t pay its workers for all the time they worked. The case involved FLSA and Arkansas Minimum Wage Act claims.

The first proposed settlement called for Baldor to put up funds totaling $105,500 for class members who then had to file claims to receive their settlement. Under the proposed settlement, the plaintiffs’ lawyers would ask for $52,000 in attorneys’ fees and Baldor wouldn’t object.

Holmes denied the proposed settlement, calling it “problematic” that class members who failed to file a claim would not be paid their share, which Baldor would get to keep. “The Court expressed concern that many employees would not submit claim forms, leading to the employees waiving their [Arkansas Minimum Wage Act] claims, but receiving no compensation,” Holmes wrote in an order filed June 28.

Holmes asked the lawyers why the proposed settlement required class members to submit claim forms rather than simply having Baldor mail them checks.

Both sides agreed for checks to be mailed to all class members without requiring them to file claims, Holmes said in the order.

But when a second proposed settlement was submitted, it didn’t “follow the proposed course of action set out by counsel at the hearing,” he wrote. Under the new terms, class members would receive half of their settlement money if they did nothing, but would have to submit forms to receive the balance.

Holmes also rejected that settlement, saying it wasn’t “fair, adequate, and reasonable.” He set a bench trial for Oct. 22.

Sanford told Arkansas Business that he couldn’t predict if the Baldor case will settle before the trial. “At all times we act with our clients’ best interests at heart, and there is no allegation that we do not,” Sanford said in the email.

And he said the litigation has already made a difference at Baldor because the manufacturer of industrial electric motors “corrected some of its time clock policies.” “Even though the lawsuit is still ongoing, today workers at Baldor’s facilities are getting paid for work that they were doing off-the-clock in 2017,” Sanford said. “The law firm is proud of that result, even if we have not been paid for our work.”

Centerfold Cases

Holmes also took exception to work Sanford did in two cases against Centerfold Entertainment Club Inc. of Hot Springs. Rauls was not involved in those cases. In 2017, Holmes nixed a proposed settlement that called for Sanford and another attorney from his firm, Joshua West, to collect $5,000 in attorneys’ fees while their client, a bouncer, would receive $1,000.

“Based on the limited information provided, the Court finds that the proposed settlement agreement in this case is neither fair nor equitable to all of the parties,” Holmes wrote in the July 2017 order.

Holmes denied the request to approve the settlement and then dismissed the case, since the plaintiff wanted to “avoid trial at all costs,” he wrote.

Sanford and West filed another suit in 2014 on behalf of exotic dancers who said they were not paid a minimum wage or overtime while they worked at Centerfold. After a four-hour bench trial last year, Holmes awarded three women a total of $71,000 for back wages and damages.

Sanford and West asked Holmes to award them $123,500 for costs and attorneys’ fees. The bill claimed that Sanford, West and other attorneys and paralegals at the firm devoted nearly 500 hours to the case.

Holmes questioned the bill.

“Based on its experience, the Court is hard-pressed to find that a collective action trial lasting four hours with five witnesses, and virtually no documentary evidence would take 496.6 hours to litigate,” he wrote in a September 2017 order. “There were only four exhibits received into evidence, which consisted of Defendants’ Facebook pages and tax returns.”

Holmes said in the order that he didn’t believe the total hours spent on the case were reasonable.

He awarded Sanford and West $37,774, less than a third of their requested fee.

Despite the judge’s findings, Sanford said, his law firm won’t change the way it handles cases in front of Holmes.

“The Sanford Law Firm represents its clients professionally and follows court rules in all cases, and we will continue to do that,” he said in the email. “We don’t agree with all of Judge Holmes’ decisions, but we believe he is dedicated to treating our clients and everyone else who comes before his court fairly.”