The end of Preferred Family Healthcare’s implosion in Arkansas, which jolted the state’s Medicaid service industry and scarred its political landscape, came not with a bang, but with a text.

A text message from PFH, the Missouri nonprofit stripped of its Arkansas Medicaid business over a bribery and fraud scandal, cleared the way for a Hot Springs nonprofit’s bid to buy PHF’s assets, according to Casey Bright, CEO of Quapaw House Inc.

Bright told Arkansas Business last week that PFH reached out with a message last month asking if the Hot Springs company would be interested in acquiring some of PFH’s Arkansas assets. Bright’s reply: “We’d be interested in all of them.”

Quapaw House, which had over $8 million in revenue last year, now has an agreement in principle for all those assets, Bright says, including 47 PFH service sites around the state. It also hopes to hire hundreds of PFH employees.

“Two text messages and a phone call meant that we were off and running,” Bright said.

The acquisition, which was expected to be finalized late last week, would offer some stability for the 5,200 Arkansas Medicaid clients who get behavioral health and addiction treatment from PFH, based in Springfield, Missouri.

The deal also adds a coda to a tale packed with political corruption, cash-stuffed envelopes and even a meeting with a purported contract killer.

Quapaw House, which has about 160 employees, heads a list of behavioral health companies lining up to fill the void left by PFH, once the state Medicaid program’s largest provider of counseling for troubled youths and adults.

In the 2018 fiscal year that ended June 30 just as the Arkansas Department of Human Services was cutting off Medicaid payments to PFH, the company had $30 million worth of contracts with the state.

PFH grew into one of the Midwest’s largest behavioral health organizations through a merger with Alternative Opportunities of Springfield in 2015 and was riding high back then. That was before federal corruption cases toppled notorious lobbyist Milton “Rusty” Cranford, a half-dozen Arkansas legislators and eventually PFH’s Arkansas operation.

Now Quapaw House, or QHI, plans to be a subcontractor for local Medicaid service agencies that have taken over PFH’s contracts. Bright said QHI offers inpatient services that most local providers can’t offer.

“We’re going to subcontract with the local providers who now have those contracts, and we’re already working toward providing those services,” Bright said in an interview on Wednesday. “We depend on working with those providers; it’s part of our business plan. But there’s still a lot of work to be done.” QHI, which has two dozen facilities, must work with the state on licensing, credentialing and certification before fully taking over PFH sites scattered across the state, from Rogers to Lake Village, Paragould to Texarkana, Harrison to El Dorado.

“The goal is for QHI to begin operating these assets on or around Oct. 12,” Bright said in a Sept. 14 statement, citing a shutdown date DHS has set for PFH in Arkansas. “QHI will continue operations in the same manner as PFH is now doing and as it has been doing in the past until an integration plan is developed … We hope to continue providing quality services to the current PFH clientele, and for the dedicated PFH staff to join the QHI team.”

While PFH has been reported to have some 700 Arkansas employees, Bright said the actual number is now smaller, between 400 and 500. As Arkansas Business’ print deadline approached Thursday, Bright said he couldn’t disclose a sale price for the assets. Several calls seeking an update from Bright on Thursday went unanswered.

“At the end of the day, you’ll see it’s not an unreasonable amount for a company our size,” he said. “It’s not a business we’re buying, but rather the assets, and building a business off that.”

Corruption Fallout

The acquisition effort comes as Cranford, the corruption saga’s central villain and a former PFH executive, sits in a Missouri jail cell awaiting sentencing on bribery charges. A poster boy for persistent “good ol’ boy” politics in Arkansas, Cranford was arrested by federal agents in Bentonville in February.

They found 177 $100 bills in a backpack and bottles of Xanax and hydrocodone pills for which Cranford had no prescription, along with a .45-caliber derringer-style pistol. After first fighting the charges, Cranford capitulated with a plea deal in May. As investigators closed in, authorities say, Cranford tried to solicit an old family friend-turned-FBI-informant to kill a co-defendant giving evidence against him.

Six former Arkansas lawmakers who worked with Cranford were implicated in his dealings, and four — Jon Woods of Springdale, Eddie Cooper of Melbourne, Hank Wilkins IV of Pine Bluff and Micah Neal of Springdale — have been convicted or pleaded guilty. Many of the players are also ensnared in a separate kickback case involving state grant money that flowed to Ecclesia College in Springdale.

Jeremy Hutchinson, a lawyer and nephew of Gov. Asa Hutchinson, hasn’t been charged in the PFH fiasco, in which he was paid $500,000 by the provider and others affiliated with Cranford, ostensibly for legal work. But he resigned from the state Senate on Aug. 31 after being indicted by a federal grand jury on 12 wire and tax fraud charges alleging that he spent campaign contributions on personal expenses and falsified campaign reports and tax returns.

The state cut off PFH’s Medicaid reimbursement spigot in June after Robin Raveendran of Little Rock, a former PFH vice president described in an affidavit as “one of Cranford’s closest associates,” was charged in a separate $2.3 million state Medicaid fraud case filed by Attorney General Leslie Rutledge.

Another Cranford crony, Jerry Walsh, pleaded guilty in July to federal conspiracy charges for steering funds from the nonprofit South Arkansas Youth Services of Magnolia to Cranford and an unnamed state senator for their influence in protecting the nonprofit’s DHS contracts.

Two more former PFH executives have pleaded guilty to embezzling from the nonprofit, as has a political operative from Philadelphia, and prosecutors described other former executives at PFH and Alternative Opportunities as “co-conspirators.”

Looking Ahead

On its website, PFH declares that it is not the target of any criminal investigation, and “in fact we are cooperating with government authorities regarding investigations into the misdeeds of several former leaders and employees.”

But Bright is looking ahead, rather than to the past, as QHI works to start serving Preferred Family Healthcare’s former patients. “I just want to stress that our company is completely separate from Preferred, because some people have been asking about the connection. PFH is a group out of Missouri, and they’ve been good to work with, but we’re not connected to them in any way. We would just like to acquire their assets and serve their clients, and to be as transparent as possible.”

Preferred Family Healthcare issued a Sept. 14 statement saying it had notified DHS of its intent to cease operations in Arkansas, as well as its commitment to employees and clients to “work toward a smooth transition for all involved.” The company, which will continue operations in Missouri, Oklahoma, Kansas and Illinois, said its officials were “pleased when QHI reached out this week, and while we are continuing with our [transition] plan, we look forward to finalizing ongoing discussions toward an agreement to acquire our assets.”

Marci Manley, deputy chief of communications at DHS, said the state was aware of QHI’s pending deal with PFH. But her agency’s role in any deal is negligible, she said, limited to concerns like making sure that all Medicaid requirements are met and that every PFH client has an individual transition plan.

“These are two private entities discussing a business transaction, so our part is limited to the general kind of advice and certification help that we would give to any interested provider,” she said. “There are steps that need to be followed for providers looking to expand in these areas; it’s not just a matter of taking over.”

Bright said the first step “basically for all sites is that we’ll have to apply for licensing and certification, then get to providing services for as many people as quickly as we can.”

He noted that Quapaw House has been an Arkansas operation for 49 years. In his 11 years in charge of the nonprofit, Bright said, annual revenue has grown eightfold to more than $8 million. It was looking to expand even before the PFH opportunity arose. He noted that substance abuse treatment doesn’t pay as well under Medicaid reimbursement as mental health counseling, something that QHI hopes to offer to PFH’s former clients.

“We’ve got 380,000 SF of facilities, and our expansion has to be strategic, so we were looking at adding about 12 additional facilities under the earlier plan,” Bright said. “We considered sites in El Dorado and Texarkana before this opportunity came up, but this acquisition will accomplish that goal and give us more opportunities to work with partners.”

Scorecard for a Scandal

A nonprofit based in Springfield, Missouri, PFH announced in August that it would be shutting down on Oct. 12 in the wake of the state canceling its contracts and stopping Medicaid reimbursement amid a bribery and fraud scandal. The company announced on Sept. 14 that it was finalizing an agreement for Quapaw House Inc., a Hot Springs nonprofit Medicaid provider, to acquire its assets in Arkansas. Its operations in the state include 50 clinics and service sites, including Health Resources of Arkansas, Decision Point in Bentonville and the Wilbur D. Mills Treatment Center in Searcy. The PFH website, PFH.org, includes a banner link to transition services for its clients in Arkansas.

The PLAYERS

RUSTY CRANFORD

An Arkansas lobbyist and former executive vice president of PFH, Cranford is in a Missouri jail awaiting sentencing for crimes related to his bribery of at least four lawmakers. When he was arrested in May, federal agents found $17,700 in cash, unprescribed pills and a derringer-style pistol. He pleaded guilty in June as the central character in a scandal that David Ramsey, writing in Arkansas Times, memorably described this way: “At various times over the last five years, Arkansas’ government was taken hostage by a criminal enterprise.”

JON WOODS

A former state senator from Springdale, Woods reported to federal prison last week to begin a whopping 18-year sentence. He was convicted of 15 counts for his role in a conspiracy to give kickbacks on state grants provided to nonprofits at his direction. He was also ordered to pay $1.6 million in restitution. He pushed a $275,000 state grant to a nonprofit incorporated by Cranford, and received kickbacks, prosecutors say. PFH also arranged for Woods’ fiancee to get a job with a PFH affiliate at inflated pay.

EDDIE WAYNE COOPER

A former state representative from Melbourne, Cooper pleaded guilty to embezzling from PFH, where he worked as a regional director. In his plea in February, he admitted conspiring with Cranford and other company officials to “embezzle, steal, and unjustly enrich themselves” to the detriment of the nonprofit and its clients.

HANK WILKINS IV

A former state representative, state senator and Jefferson County judge, Wilkins pleaded guilty to accepting $80,000 worth of bribes from Cranford, mostly in the form of “donations” to St. James United Methodist Church in Pine Bluff, where Wilkins was pastor. He steered some $245,000 in state funds to his co-conspirators, according to the U.S. attorney’s office in Little Rock.

MICAH NEAL

A former state representative from Springdale, Neal’s “pipe dream” came true Sept. 13 when U.S. District Judge Timothy Brooks spared him any prison time for his guilty plea to conspiracy. The fraud case involved a $38,000 kickback in a scheme involving state grants to Ecclesia College in Springdale. Neal, who was accused of accepting kickbacks from Cranford, got sentencing credit for the “pivotal role” his cooperation played in obtaining convictions or guilty pleas from his three co-conspirators.

JEREMY HUTCHINSON

Hutchinson, a former state senator from Little Rock, nephew of Gov. Asa Hutchinson and son of former U.S. Sen. Tim Hutchinson, resigned from office after he was indicted on fraud charges based on misused campaign funds. He was also paid more than $500,000 from 2012 to 2017 by PFH, Cranford and some of Cranford’s other clients. Hutchinson’s attorney has described it as payment for legal work, and Jeremy Hutchinson has not been charged in the PFH inquiry.

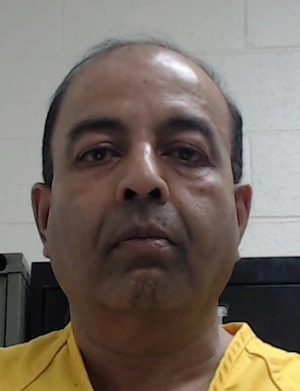

ROBIN RAVEENDRAN

A former PFH vice president, Raveendran was charged by state Attorney General Leslie Rutledge’s Medicaid Fraud Division, accused of some $2.3 million in improper billing. He formerly led the Arkansas Department of Human Services’ Program Integrity Unit, which Rutledge says gave him insight into how to game the system. He has pleaded not guilty.