In a quarter-century of municipal leadership, Chris Claybaker rarely championed a city project as bold and meaningful as Clarksville’s deal to build Arkansas’ first hydrogen production and power plant.

The former Camden mayor and Berryville economic developer retired from city government in August and now is a development principal with Syntex Industries LLC, the Little Rock company that announced an agreement with the city of Clarksville this month to build the plant. He described a $150 million first phase of a three- or four-phase project that could add up to a billion-dollar investment.

“We’re really excited about the chance to be part of the energy transition for cities to become carbon neutral,” said Claybaker, a former president of the Arkansas Municipal League. “I’m starting to get that sense of accomplishment that I haven’t felt since I was mayor of Camden.”

The Clarksville plan calls for solar power arrays and purchased renewable energy to fuel the production of green hydrogen, which would then be burned to drive conventional electricity-generating turbines or be fed into fuel cells to create electricity, officials told Arkansas Business last week.

The first phase would supply about 50 megawatts of power for Clarksville, which was the first Arkansas city to power its operations 100% with renewable energy three years ago. But power demands have grown, and Clarksville is eager to regain its energy independence. The plant’s affordable renewable electricity would also help lure power-hungry companies to town.The plant will eventually ramp up to a capacity of 500 megawatts, much greater than any hydrogen plant now operating in the U.S.

The project is the brainchild of Syntex Managing Director and CEO Tom Waggoner, the former managing director of Community Solar Partners of Rogers and founder and former CEO of publicly traded Staar Surgical Co. of Monrovia, California, which has a market capitalization of nearly $3 billion.

“We expect to have the first phase up and operating in less than two years,” Waggoner said last week. “That phase, basically, will allow Clarksville to become independent in their sourcing of their power and self-sufficient. The second phase will probably come in within a year after that. In order to justify expanding to that, we’ll have to have one or more of those businesses come in. We don’t have to, but the economics work a lot better if we do that.”

Another economic development prospect Waggoner alluded to, a “bio-refinery” with a need for 200 megawatts of power, would be the key to proceeding with the third phase. “That’s the reason we’re looking at the 500 megawatts,” he said.

Pioneering City

City-owned Clarksville Connected Utilities made headlines with Scenic Hill Solar CEO and former Arkansas Lt. Gov. Bill Halter after solar arrays turned Clarksville into the state’s first renewable-powered city government in 2020. And Scenic Hill is one of several solar development companies Syntex has in mind for the new project, Claybaker said. Contractors are also interested in the construction job, although Syntex and the city are keeping their identities confidential.

In a telephone call, Halter said he couldn’t speak on potential projects.

Claybaker said a site has been picked and property is under contract for the plant, but he couldn’t discuss specifics because some details are pending.

This month, Clarksville announced its memorandum of understanding with Syntex, describing the Syntex Hydrogen Power Plant as an economic development lure for the Johnson County town of about 10,000. The city and Syntex expect the plant to be a kind of electromagnet for businesses and a model for other cities.

“I’m in my second term, and I’m learning that power is a major decision factor for companies to choose your area,” Clarksville Mayor David Rieder said in a telephone interview. “Is it affordable? Is it reliable? Is it resilient? Companies want to know a lot of things before bringing their manufacturing and resources into a community.” Rieder said recent extreme weather events that have knocked out power in Texas and elsewhere demonstrated the economic need for the dependability of hydrogen energy.

“The whole city of Clarksville runs on 25 megawatts of power, and one new facility [attracted to the city] might consume 250 megawatts. So this is a big step to execute something like this for a community of our size. It will also create the kind of jobs that will keep our next generations from moving out of the area.”

The Clarksville project has several options for financing, Claybaker said, but it won’t be reliant on the Biden administration’s $8 billion push for regional hydrogen “hubs.” Arkansas has partnered with Louisiana and Oklahoma with a “HALO Hydrogen Hub” proposal that was among 33 nationwide that drew encouragement in December from the U.S. Department of Energy to compete for slices of the funding.

Syntex expects to break ground on the project by the end of this year, and the plant will employ more than 100 full-time workers after the initial phase is completed, Claybaker said.

Making and using hydrogen is seen as an essential technology for decarbonizing a rapidly warming Earth. It is also a key initiative in the administration’s effort to reach a 100% clean electric grid nationally by 2035 and its grander goal of net-zero carbon emissions in the nation’s economy by 2050.

Mayor Rieder said Syntex and Clarksville are developing ways to store excess renewable energy and regenerate it on demand. “Recent technical developments and federal tax incentives opened the door,” he said. “This project offers infrastructure to support our growing economy and bring new high-paying ‘ecodustrial’ jobs to the area.”

Waggoner hopes to build a hydrogen power grid infrastructure rather than one large central hydrogen hub as Arkansas joins the race to develop clean energy and an innovative fuel for transportation.

The Clarksville plant will create its own hydrogen, partly because the element is hard to transport. With a relatively low volumetric energy density, it takes up much more space than, say, natural gas. Transport requires storing hydrogen in pressurized tanks or liquefying it at extremely low temperatures. But hydrogen can also be stored in compounds like ammonia and methanol, then “cracked” to release the hydrogen from the compound.

Syntex plans to use either methanol or ammonia as its storage agent, Claybaker said.

Trucks, Ships and More

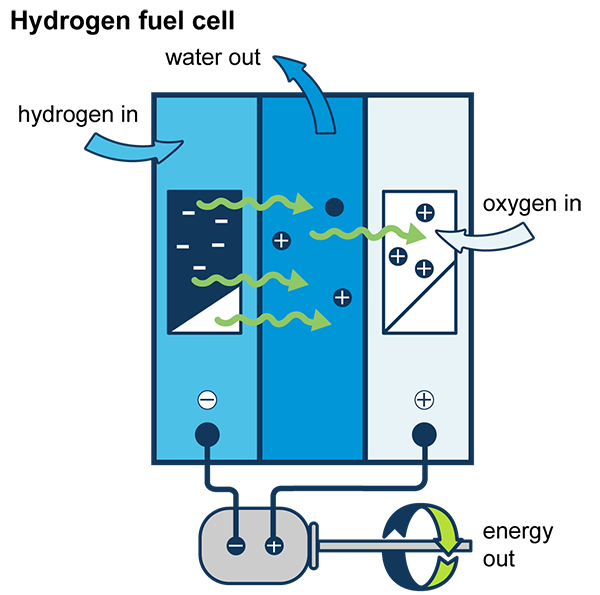

Hydrogen fuel cells produce power by joining hydrogen and oxygen atoms, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The hydrogen reacts with the oxygen across an electrochemical cell “to produce electricity, water and small amounts of heat.” Trucks and trains using small hydrogen cells are in development, and ships fueled by hydrogen or ammonia are also testing the waters.

The Clarksville project is timed to correspond with a ballooning global demand for hydrogen, which set a record of 103 million tons in 2021, according to the International Energy Agency. Low-emission hydrogen, however, has been a minuscule part of the market. That is expected to change, though, with the IEA predicting that low-emission hydrogen may command 25% of the world market by 2030.

Waggoner, the Syntex managing director, called Clarksville exactly the kind of “progressive community” for a big hydrogen project.

“This is a leading edge of a major mega-trend in the energy transition as we move from a carbon-based to a hydrogen-based economy,” Waggoner said. “We really think Clarksville has the potential to become the heart of a Hydrogen Valley in Arkansas. Much as the developments in Palo Alto in Silicon Valley created the digital transition 50 or 80 years ago, we’re seeing an energy transition that could make Clarksville a key mover… And it won’t stay just in Clarksville. It’s going to move up and down the valley.”