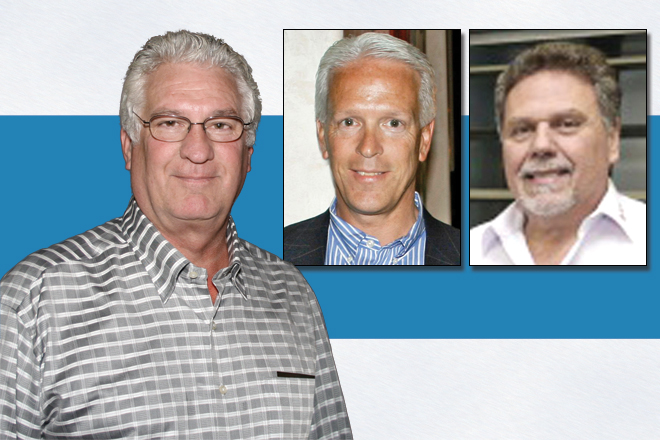

Former One Bank & Trust CEO and President Layton "Scooter" Stuart (left), who died March 26; Gary Rickenbach (center), former executive vice president and chief loan officer; and Alberto Solaroli (right) of Jacksonville, Fla.

A nonperforming loan in Florida helped lead to the ouster of Layton “Scooter” Stuart, former chairman, president and CEO of Little Rock’s One Bank & Trust.

Through a strange turn of events, the bad loan in the Sunshine State brought Stuart into deeper controversy when he built a million-dollar manor for his son, Hunter. The Florida debt and west Little Rock house are entwined in the web of loans, cashier checks and self-dealing at One Bank.

Accounts from Stuart, who died on March 26, and Gary Rickenbach, former executive vice president and chief loan officer, provide the narrative link for the two seemingly unrelated items.

In January 2009, Stuart planned to use debt-free property near Little Rock’s prestigious Edgehill neighborhood as collateral to finance his son’s upscale project in Pleasant Valley. Instead, the three residential lots on Crestwood Drive, owned by Scooter Stuart’s Crestwood Investment LLC, were mortgaged for $1.1 million and the proceeds used to financially mask a nonperforming loan in Florida.

“Mr. Stuart participated [in covering the bad loan] via a real estate-secured loan and effectively made a capital contribution to the bank,” Rickenbach wrote in an internal memorandum dated Sept. 30, 2012.

“The Crestwood loan was presented to and approved by the board due to the insider nature of the loan, but my loan presentation did not clearly state the use of the proceeds and was misleading to the board.”

Stuart agreed to let Rickenbach use his Crestwood property as collateral as long as it didn’t interfere with his efforts to purchase a home for his son.

“I told them I need access to cash, as I had plan[s] to buy Hunter a house and remodel, so I agreed to a 90-day deal, with one extension,” Stuart wrote to an associate in an email dated March 24, two days before his death. “But in any case, I was to have full access to the collateral and/or cash to use on the home purchased for Hunter.

“They made me feel fully comfortable they could cover any cash needs I would have, so I agreed but never knew what happened after that.” “They” are Rickenbach and Michael Heald, whom Stuart fired as executive vice president and chief operating officer in August 2011.

This professed ignorance would ultimately cost Stuart in regards to the money used to pay for the construction costs of the Pleasant Valley home.

Solaroli Loan

The bad loan that brought Stuart and his Crestwood Investment into play totaled about $1.5 million. Rickenbach had made the loan to Alberto Solaroli, a one-time Porsche-tuning shop owner in Toronto who became a purported mechanical innovator after moving to Jacksonville, Fla., in 2005.

Solaroli claims to hold a breakthrough patent on a “pseudo adiabatic engine” that is more than twice as efficient as conventional engine technology. These days, the 59-year-old is listed as CEO of the USA operations for the Slovakian-based Revolutionary Technologies United LLC.

The cast of characters in the out-of-market loan to Solaroli included two denizens of the Little Rock investment community: Ernest Bartlett III and David Crews.

Crews, an executive vice president at Crews & Associates at the time, referred the Solaroli loan to One Bank and received some of the proceeds, according to Rickenbach.

Crews, the son of the investment firm’s namesake founder, couldn’t be reached for comment. He is no longer with Crews & Associates.

Bartlett’s connection to the Solaroli loan is more quizzical. He couldn’t be reached for comment either.

“Mr. Bartlett was not involved in the Solaroli loan whatsoever, but offered to assist in the resolution of the loan out of a sense of ‘doing right’ when an investor like Crews refers a deal to a bank,” Rickenbach wrote. “At the time, Crews and Bartlett were friends and periodically co-invested in equity investments, and Mr. Bartlett was aware of the outcome of the Solaroli loan.”

(Bartlett made news in July when allegations of securities fraud were leveled against him and others in a cease-and-desist order by Arkansas Securities Commissioner Heath Abshure in connection with Bamco Gas LLC. Bartlett allegedly deceived investors during the sale, through Crews & Associates, of $17 million in debentures in the defunct oil and gas exploration company. The order also detailed Bartlett’s checkered past: the National Association of Securities Dealers in 1989 barred him from association with any NASD-registered broker-dealer in any capacity.)

The Solaroli loan was paid off in 2009 instead of written off thanks to the $1.1 million loan to Stuart’s Crestwood Investments and loans of unspecified value to Crews individually and to Bartlett through Ox Investments LLC, according to Rickenbach’s memo.

One Bank had obtained a nearly $1.6 million judgment against Solaroli in July 2008. The delinquent loan was originally secured by worthless shares in Solaroli’s penny stock venture: Infinite Networks Corp.

“As we pressed ahead with legal action, it was becoming apparent that our collateral would not be able to liquidate the loan, and the bank faced the prospect of a significant loss,” Rickenbach wrote. “Rather than incur such a large loss, I was asked to come up with a solution to resolve the situation.”

The Solaroli loan was a dominant topic in the four-page memo addressed to the One Bank board of directors that also served as a confessional of sorts for Rickenbach and a plea to keep his job.

“It is my desire to be allowed to remain in my current position to continue to help the bank work through these very difficult times we currently face,” he wrote.

Rickenbach was let go in February, the last in a string of top executives replaced at the financially challenged bank.

In the memo, Rickenbach describes an elaborate juggling of money through various accounts to keep current the loans that were used to cover the Solaroli loan.

“While too complicated to be enumerated here, after the first year, interest payments on the three loans have for the most part been paid via accounting transfers from the bank,” Rickenbach wrote. “These transfers were requested by me, which resulted in deposits into checking accounts at One Bank that were then used to pay the interest due.

“While no funds left the bank (i.e. unrecognized income offset by payment of interest income), the maintenance of the loans in this manner was improper and did not clearly reflect the true purpose of the loans.”

Another loan to Bartlett’s Ox Investments was used to advance funds to make a principal and interest payment on Stuart’s Crestwood Investment loan, according to Rickenbach. He said this arrangement was misleading and not properly disclosed to the board during the renewal of the Crestwood loan in 2011.

“There is little justification for my actions in this situation, only my desire to resolve a problem loan that I made and was instructed to deal with. No monies from any of these activities were ever used for me personally, but clearly, I have not been fully forthcoming with the details of each loan, and the loans have not been serviced properly.”

Who Knew What?

Stuart’s email indicates he didn’t know the Crestwood Investment loan was actually a one-year agreement, at least initially. The loan was renewed annually until the Crestwood property was sold in two transactions last year in September and November.

The combined sales repaid One Bank in full.

“It was a maze of loan[s] that Heald and Rickenbach refused to explain,” Stuart wrote.

This maze ties in with the 5,328-SF Pleasant Valley home built at the direction of Stuart.

One Bank took possession of the property from Hunter Stuart last month. Ownership was transferred to the bank to settle a lawsuit over the money backing the residence.

In its 44-page forfeiture action against Stuart, the U.S. government alleged that fraudulently obtained bank funds in excess of $1 million were used to buy the west Little Rock property and build a house.

Did Scooter Stuart know that money he received from One Bank to cover construction costs on the Pleasant Valley residence stemmed from bills for phantom work on bank branches, as alleged by federal investigators?

Stuart offered his take on the financial labyrinth around the project as part of the March 24 email.

Stuart came short of admitting that he was responsible for the fraudulent paperwork used to obtain a $360,000 loan from One Bank in his son’s name with which to buy the $450,000 property.

He flatly denied knowing that the $96,897 used to make the down payment and closing costs came from the bank’s operating account. Stuart said he thought the money came from one of his accounts at the bank.

“I just asked [Tom] Whitehead [chief financial officer at One Bank] for two cashiers checks, no instruction as to which bank account to charge them to,” Stuart wrote.

According to the government’s forfeiture complaint, the money was improperly accounted for as advance payments to vendors.

Stuart wrote that he was solely responsible for the Pleasant Valley deal and oversaw all aspects of the construction work, including payments to subcontractors.

“Hunter had no knowledge, involvement, planning, contact with any subs, etc.,” Stuart wrote. “He just did what he had naturally done for [the] last 27 years, rely on his dad to provide and to do the right thing.

“Yes, he is [the] legal owner, but all contracting, planning, work with subs, payments to subs came from me, Layton Stuart.”