State Sen. Jane English has no use for the private option, the Medicaid expansion providing health insurance to the poor.

But the Republican lawmaker from North Little Rock saw an opportunity and took it, and what began as an old-fashioned political horse trade — you get my vote, I get something for my constituents — appears likely to evolve into a governor-backed legislative package that next year will seek to transform workforce training in Arkansas.

That’s because English would rather see the poor move out of sometimes multigenerational poverty into a job; so would Gov. Mike Beebe. At the same time employers in Arkansas, particularly manufacturers, want a workforce that will show up for work and know how to use a ruler. (See Changing Face of Manufacturing Leads to Skills Gap, Job Opportunities.)

These wishes are on track to coalesce into a broad-based effort involving state agencies ranging from the Department of Correction to the Department of Higher Education to the Arkansas Economic Development Commission, along with the Arkansas Association of Two-Year Colleges and the Arkansas State Chamber of Commerce, among others.

All because one woman, grown tired of the status quo, sought to move beyond political party and individual turf to what is good for the state as a whole.

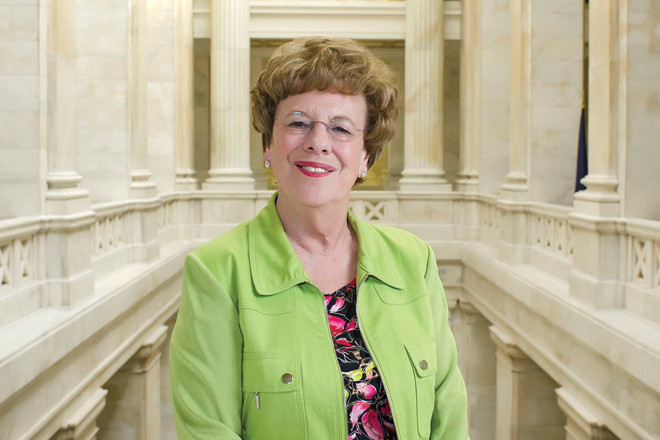

“We continue to go down the same path, but we don’t change,” English said in an interview last week in the state Capitol. “Where is our vision for what we want to be 20 years from now or 25 years from now? For my grandchildren and for your grandchildren, what do we want to be? I don’t want to be 49th forever.”

The interview came four days before she was scheduled to meet with much of Beebe’s cabinet as well as a couple other key Republican state senators to discuss worker education reform. It’s reform that English envisions eventually involving every aspect of education, from K-12 to higher ed to career ed to state-sponsored job training programs.

The interview came six weeks after English agreed to become the swing vote approving an additional year of funding for the private option in exchange for the state implementing worker education reform.

Inside and Out

English went to work for what was then the Department of Economic Development in 1984, staying there 15 years, most of the time, she said, recruiting industry to Arkansas. During her time at the department, English became involved with the closure and realignment of military bases, a result of the end of the Cold War, on the national level.

She later went on to become director of the Fort Chaffee Public Trust, another outgrowth of the federal effort to downsize the military, and later worked as director of the Arkansas Manufacturers Association. But in 2001, the association disbanded, citing the recession and the continued decline in manufacturing in the U.S., and then-Gov. Mike Huckabee invited English, now 73, to join his cabinet as director of the state Workforce Investment Board, where she served a little more than two years.

“And then I just kind of retired and got into politics,” said English, a Nebraska native. “I said listen, I tried to change the world from the inside and it doesn’t work.”

In 2008, she was elected to the Arkansas House, serving District 42 for two terms. She went on to be elected to the state Senate, representing District 34.

English, who is married and the mother of a grown son and daughter, chairs the Joint Performance Review Committee, the State Agencies & Government Affairs – Senate Constitutional Issues Subcommittee and the Veterans’ Home Task Force.

When she was working at the state Department of Economic Development, English said, the only thing that companies considering moving to Arkansas were seeking were low taxes and low wages.

“As time went on,” she said, “what became more evident is that … people were looking for people with greater skills. And we didn’t have a coordinated effort to try and make that happen.

“We talk a lot about education and economic development, but what does that really mean?” English asked. “Nobody can define that. And our focus has sort of always been, ‘We need to send everybody to college.’ Well, that doesn’t work for everybody.”

The state has an abundance of worker education programs, “but they all kind of operate in silos,” English said.

In one silo, she said, is K-12 education, getting billions of dollars. “And we have higher ed over here, and they’ve got football teams and basketball teams and lots of money and lots of lobbyists.

“And then in the middle here are the rest of our citizens,” English said, some of whom may not have even completed high school.

In addition to public education are a variety of job training programs run by the state. Among these are programs operated by AEDC, the Department of Workforce Services, the Department of Career Education, the Department of Human Services and the Department of Correction.

Some of these programs are effective, English said, but coordination is lacking, leading to duplication of services.

Also lacking, she maintains, is state outreach to business and industry, an effort to make them partners in worker education on every level of that education. “We talk a lot about career and technical education in high schools, but I’m not convinced that there is the business input into those career and technical things,” English said.

And, of course, resources are an issue. The programs that work, those that give workers the skills they need to then land a job, should have more money.

On these issues English and state officials are largely in agreement: Workforce training reform means improved coordination of programs, elimination of duplicative programs, meaningful industry input into training efforts, measurement of program effectiveness and more money for programs proven to work, $15 million in fiscal 2015 to be administered by the AEDC.

All Aboard

“It was fairly refreshing to see somebody come in and say, ‘I think I can see a way clear to doing what you want, but I want something in return,’ and the something in return was a true statewide need,” said Grant Tennille, executive director of the Arkansas Economic Development Commission.

Efficiency is what workforce training reform is about, he said. And the need for efficiency is demonstrated by the fact that apparently nowhere in state government is there one agency or one official who can list all the state-sponsored workforce training programs. “That has long been part of the problem,” Tennille acknowledged.

“Now, the governor instituted the workforce cabinet at the beginning of his tenure, and there has been a whole lot more collaboration and communication than there ever was in the past,” he said.

Nevertheless, difficulties remain. Funds, for example, are “siloed” just as programs are.

A 0.5 percent tax levied by the state on corporate income of more than $100,000 currently brings in about $24 million annually. Originally envisioned for workforce training, over time that money became part of the funding formula for two-year colleges, Tennille said.

The governor’s legislative package will include efforts to ensure that money goes toward workforce development.

By refocusing this money on job training and through other reallocations of funds, “we think we’re going to be able to create a pot that should amount to something between $24 million and $32 million a year,” Tennille said.

The key, he said, will be to give the two-year colleges the ability to be more “nimble,” to be able to respond to business and industry demands for certain workplace skills.

As for English, she said that “ever since I’ve lived here, we’ve talked more about how do you get people onto some of these social programs than about how do you get them off.” That, she thinks, is the wrong emphasis.

“I think we have good people here in the state who would like very much to have a good job, would like to be able to have the skills to be able to go and do a good job. Buy a house, buy a car,” English said. “I still believe in the American dream.”