Tell Roger Williams that a multibillion-dollar plant for turning natural gas into liquid fuel near Pine Bluff sounds too good to be true, and he’ll turn to history, engineering and finance to argue it’s too good not to be.

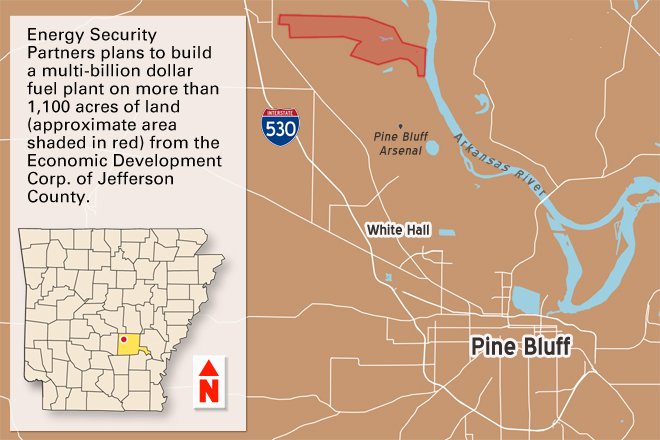

Williams, whose company spent more than a year securing 1,100 acres in northern Jefferson County for what would be the largest construction and economic development project in Arkansas history, marshals all those subjects to make a case that his plan isn’t even risky. With skills he learned in years of energy law, he offers his risk summation:

“On a risk scale of 1 to 10, drilling a well in deep water in an unexplored area would be a 10; you invest $100 million to see if anything is down there, and your chances are typically less than 10 percent,” he said. “That’s high risk. At the other end, building a pipeline is a 1. It’s been done many times, the risks are known, and it’s simply execution. So if you look at those two extremes, we would view our project as probably close to a 2. We have an established technology, we’re working with the most reputable contractors, and we have reputable buyers for our product. This is not a risky project.”

That doesn’t mean that Williams thinks the task will be easy. As co-founder and CEO of Energy Security Partners, he has to obtain environmental permits, assemble the largest cranes in the world and deliver equipment so massive it can be moved only by river barge — not to mention raise the minimum of $3 billion needed for the first phase of construction. But Williams, a man of detail from a military family, trim and neat from well-groomed beard to impeccable blue blazer, has clearly done some homework.

A chemical engineering graduate before studying law, he speaks in quiet but enthusiastic tones over a conference table at ESP’s offices on the Little Rock riverfront. He starts by describing a nearly century-old chemical process he first encountered as an undergraduate at Vanderbilt, one that turns carbons into liquid fuel. Then he turns to the complexities of assembling big deals in the oil business, a process he learned over nine years at Exxon. Next come the minutiae of contracts and finance, which he studied in law school at the University of Alabama, and applied as an energy attorney in New York.

The culmination is an ambitious, highly detailed plan for the gas-to-liquid (GTL) plant. Economic development officials say it would bring more than 2,500 construction jobs and provide 225 permanent positions averaging at least $40 an hour in one of the most economically depressed areas of the state. In its initial phase, the plant would convert cheap and plentiful natural gas into 33,000 barrels of liquid fuel, mostly diesel, each day. The second and third phases of the plan could increase production to 100,000 barrels a day. Williams’ target for groundbreaking is “roughly two years from today.”

The plant would employ a process developed in the 1920s by Hans and Franz. Not the comedy pair who promised to “pump you up,” Williams noted, but rather Hans Tropsch and Franz Fischer, scientists in Germany who developed a process of converting coal into liquid fuel.

Germany, never rich in hydrocarbons but flush with coal, later used it to fuel its war machine. But after America’s entry into World War II, the plants converting coal to diesel in the Ruhr Valley became prime bombing targets, Williams said.

After the war, the United States experimented with converting coal to liquid fuel in Brownsville, Texas, but abandoned the project because fuel made from petroleum was then so cheap and abundant.

However, the Fischer-Tropsch process can turn any carbon feed stock — coal, natural gas, biomass — into liquid fuel, and the American shale-gas boom of this century brought natural gas to the fore as a commercially viable feeder resource.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration reported in early 2014 that five major commercial plants were converting gas to liquid fuel worldwide, and a sixth, in Nigeria, has since started production.

Shell operates two plants in Malaysia and another in Qatar. Sasol has a major facility in South Africa, and the other is a joint venture between Sasol and Chevron in Qatar, the USEIA said. The Nigeria project was developed by Chevron Nigeria Ltd. and the Nigerian National Petroleum Co.

Shell says its Pearl plant in Qatar, which it bills as the largest in the world, can produce 260,000 barrels of GTL products and natural gas liquids per day.

These projects helped to spark a dream by Williams, along with ESP co-founder Gen. Wesley Clark, to turn gas into diesel and jet fuels on a grand scale in the United States. Their eyes turned to Arkansas.

Clark, the former supreme NATO commander in Europe and presidential candidate, grew up in Little Rock and was class valedictorian at Hall High School before becoming valedictorian at West Point. Another big name behind the project, former U.S. Transportation Secretary Rodney Slater, is a native of Marianna (Lee County).

Answering Skeptics

But any grand vision brings skeptics, and doubters of the GTL project include those who think the process will not be profitable as long as oil prices are low enough to keep more traditional petroleum refining lucrative. Others see financing as an insurmountable hurdle. Another few see little more than a possible trick on the hopeful people of Pine Bluff and Jefferson County.

None of this fazes Williams. He said skeptics know little about his plan’s economics or the well-established chemical process he promotes. They are also unfamiliar, he said, with a relatively new financing model that could be the key to the whole venture.

Williams conceded that oil prices must remain at $30 a barrel or more for his gas-to-liquid fuel project to thrive. Crude oil is currently trading in the $40-plus range.

“In order to have enough to cover the cost of amortizing the capital and pay the operating costs and pay the wages and generate a profit in return, we have a formula … We want to buy our natural gas from the producers at a percentage of the crude oil price.”

Williams said that natural gas can be bought on the futures market looking as far as 15 years down the road. He and other experts, touting gas as America’s most abundant clean-burning natural resource, see only low gas prices ahead. “So as oil prices move up and down, our price for the gas we buy will move with it, and we’ll be maintaining an arbitrage margin.” The contracts that lock in that margin, he said, will ensure a steady revenue stream — something that his financing model relies on.

From the inception of Energy Security Partners four years ago, the company has been working on a plan based on “project financing,” Williams said. Not to be confused with simply financing a major project, the model is a “unique asset infrastructure financing technique,” Williams said. It has been used for major projects in the U.S., but is more common in developing countries.

“The concept of project financing is that the project’s assets themselves and all the contracts that go into the project become the collateral for the lenders’ financing package.” Thus, he said, collateral would include the project site, equipment and revenue streams.

All the contracts would back the loans — “contracts to buy the feed stock [natural gas], contracts for the technology, contracts to build the facility, contracts to sell the product, all this and all the other assets.”

Williams said ESP hopes to finance the project with up to 70 percent debt financing, with the other 30 percent coming from equity investors.

“For round numbers, let’s just use $3 billion here for the cost of this project,” he said. “If we get 70 percent debt financing, we’d have to raise $900 million in equity to $2.1 billion in debt. The final factors will be determined by the strength of the project itself — on the assets, where the project is located, the strength of the contracts … who’s buying the product. Is there risk that the buyer is going to go bankrupt and then your revenue stream stops?

“We feel strong because we have done due diligence, we know that the technology is viable and that the intellectual property for the process is almost entirely in the public domain. We’re producing a commodity product — diesel and naphtha — that we plan to sell to good, strong buyers. We hope to have more than one so that we’re not dependent on a single entity to make the economics work … We’ve already seen strong interest in supplying us gas, and we have strong entities that want to buy our products.”

Williams said his team had talked with major infrastructure investment funds based in New York and elsewhere.

“These invest $300 million, $500 million into equity for infrastructure projects like petroleum refineries, major upstream oil and gas facilities, airports, toll roads, things that require a large amount of capital. This GTL facility fits well with the infrastructure model.”

‘A Positive Signal’

Tomas Jandik, a professor of finance at the Walton College of Business at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, confirmed that the project financing model has been used around the world to provide capital for strictly defined projects with two key characteristics:

- Their cash flows must be easily predictable (or even set by pre-negotiation in the case of the gas-purchasing and fuel-sales contracts Williams envisions), and

- The project assets must be difficult to hide from the debt holders’ view. That is, these assets “must be hard to ‘steal’ by borrowers,” said Jandik, who regularly teaches project financing to his executive MBA students in Fayetteville.

“Strictly from a finance point of view, if there indeed are lenders willing to loan their funds via project financing, I would consider it a positive signal” for the GTL project, Jandik wrote in an email. “It most likely means they consider the project a reasonably low risk. Thanks to the long-term, dependable cash flows, project financing typically generates the lowest financing costs thanks to large proportions of relatively low-interest debt used to finance the business venture. Needless to say, the low financing costs, in turn, increase the chances that the project will survive and be profitable.”

Williams did not volunteer names of any potential lenders or major equity fund investors, but he said “we’ve talked to eight to 10 major infrastructure funds, just to put it that way, and there’s extremely strong interest.”

“This is exactly the kind of project they want to invest in,” Williams added. “It’s in the U.S., a stable country, and it’s in an area that needs development, Jefferson County.”

All this should come as some reassurance to Jefferson County’s taxpayers, who already have a $3.9 million stake in the project. The Economic Development Corp. of Jefferson County has committed that money, including $2.8 million for the purchase price of the land.

Despite the county’s commitment, Williams wouldn’t definitively say that Jefferson County will be the final plant site, though he strongly suggested it would be. As Arkansas Business reported last week, that lack of finality was something of a surprise to Pine Bluff Mayor Debe Hollingsworth and to economic development officials like George Makris, chairman and CEO of Simmons First National Corp. of Pine Bluff, and Lou Ann Nisbett, president and CEO of the county’s Economic Development Alliance.

The Economic Development Corp. signed an agreement March 30 to lease the land to ESP, and local officials saw the lease arrangement as ESP’s commitment to the site. Williams, on the other hand, said the final site choice would be made “in the next several months,” but added that “all the indications are that Jefferson County is going to be our home.”

He said his team loves the people and their commitment, but he also noted the logistical advantages of the site, which is in the northern part of the county near the National Center for Toxicological Research.

“The site is physically located between three interstate natural gas pipelines. It’s 15 to 20 miles from these major lines,” Williams said, naming Arkansas as a crossroads in energy transportation. He also said that the Arkansas River is crucial to ESP’s construction plans. “Being able to transport the large equipment we need for the project via river barge is critical.”

He said the two largest vessels used in the GTL conversion process, the Fischer-Tropsch reactors, are 30 to 35 feet in diameter and 120 feet tall or long. “This vessel will weigh 2,000 or 2,500 metric tons.” Lifting them into place will require the largest cranes in the world.

“From a construction standpoint, this is a big deal, and that is why river access is so important, because a vessel that size is close to the biggest you can transport.”

As part of his due diligence, Williams said, he has “verified everything” involving the transport route, including river access, the dock and bridge widths and heights. “Some have suggested that Searcy might have been an ideal location for the plant” — because the three interstate gas pipelines converge near there — “except for the fact that you can’t get the equipment in there.”

(Also see: Energy Security Partners Land Dealings Began in 2015.)

Environmental Permits

ESP is now putting together applications for two major environmental permits, among others. One is an air emissions permit regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and applied for through the Arkansas Department of Environmental Quality. Another permit, to safeguard the quality of water in several streams that run through the site, is obtained through the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

“We will use water at the plant for cooling purposes,” Williams said. “We have a plan in place to mitigate any impacts on streams and wetlands. Most of these permits are anywhere from 12 to 15 months from making the application to approval.”

Once he has the permits, Williams said, he’s confident that his team can obtain the financing and get the project built. He predicts the plant will be good not just for Jefferson County and Arkansas, but also for the country.

“We want to produce liquid transportation fuels within the U.S., from a U.S. source of feed stock. Even in this period where we’ve increased domestic oil production, we still import oil. That’s why we named our company Energy Security Partners. We have a long-term goal of being part of the solution and making sure the U.S. is energy secure.”

As to the skepticism, Williams said some questioning is understandable.

“Anything that costs $3 billion to build is going to be a complicated process … But no matter what one does, there’s always going to be doubters. We know this is a big vision, but we can also see that all the fundamentals are in place.”